The Pardoner: Theories

The Pardoner: Theories of Eunuchism and Klinefelter Syndrome

Many readers notice that the Pardoner is a little...different. Yes, it’s true that every one of Chaucer’s pilgrims is unique. What makes the Pardoner different, however, is his sexual ambiguity. Many Chaucerians assume that the Pardoner is homosexual. However, some scholars argue that the “homosexual theory” still does not explain a lot of the particular descriptions of the Pardoner. Some alternative theories Chaucerians have hypothesized over the years are the Eunuch Theory and the Klinefelter Syndrome Theory.

Eunuchism

A eunuch, in the simplest sense, is a man who has been castrated. Castration refers to the removal of testicles. [1] For a more modern application, just think of when someone takes their male dog or cat to get “fixed” or “neutered.” The effects of castration include genital shrinkage, a decrease of testosterone, loss of body and facial hair, and a loss of muscle. [2]

The Pardoner As a Eunuch

The Eunuch theory was first hypothesized by a Chaucer scholar named Walter Curry. Curry was inspired by the line: “I trowe he were a geldyng or a mare.” [4] A “geldying” is translated to “gelding,” which refers to a castrated male horse; a “mare” refers to a female horse. [4] Both references indicate a sense of femininity or lack of maleness in the Pardoner. Specifically, Curry labels the Pardoner as eunuchus ex nativitate, a medieval physiognomy term that means “one who has never reached puberty.” [5] Medieval physiognomy reveals that the key characteristics of eunuchism are the lack of facial hair and a high-pitched voice. [6] All of these characteristics match the traits of the Pardoner who has “A voys … as smal as hath a goot” and “No berd hadde he, ne nevere sholde have;/ As smothe it was as it were late shave.” [7] At first, it is easy to skim by these seemingly harmless traits. In the Middle Ages, the deepness of one’s voice and the prominence of facial hair were ways to differentiate between the sexes. [8] Deviation from these perceived notions of femininity or masculinity would often result in social isolation. [9] In this case, Chaucer carefully constructs the Pardoner’s traits to be so distinct that it actually isolates his character from the rest of the Pilgrims.

Additionally, there’s evidence that shows how much Chaucer was influenced by scientific literature of physiognomy. [10] Topics of animal and male castration were of interest in the science of the Middle Ages, and Chaucer was probably aware of it. [11] Chaucer also conversed a lot with returning English crusaders from the Near East, many of whom marveled at the Byzantine practice of eunuchism. [12]

However, there are still some skeptics and critics of this widely accepted theory. Although Chaucer was interested in physiognomy, medieval physiognomy is not really an exact or accurate science. [13] There are a lot of errors in this field, and any evidence based on these studies would be unreliable. Eunuchism may have also just been used to better understand or explain homosexuality or bisexuality. [14] Additionally, castration was not well-known by the lower class or middle class, which was the audience that Chaucer wrote the Tales for. [15]

Klinefelter Syndrome

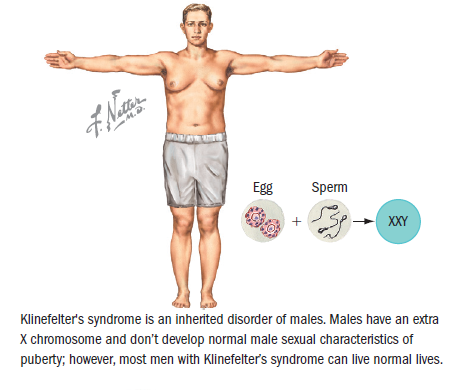

Klinefelter syndrome, on the other hand, is a genetic condition where a male is born with an extra “X” chromosome––the chromosome that determines whether one is born male or female [16]. In its simplest sense, Klinefelter Syndrome causes males to develop more feminine features. Examples of these features would be traits like smaller testes, a smaller penis, breast enlargement, higher-pitched voice, and reduced body hair. [17] Klinefelter syndrome is inherited and, unlike eunuchism, is solely due to biological reasons.

Klinefelter syndrome is often confused with hermaphroditism. While hermaphroditism refers to being born with both female and male sex organs, people with Klinefelter syndrome are born with one sex organ (male or female) but have an extra “X” chromosome which causes abnormal development of typical biological male characteristics. [18]

The Pardoner: A Case of Klinefelter Syndrome

The Klinefelter syndrome theory stems from Beryl Rowland’s theory of the Pardoner as a hermaphrodite. [20] This theory was rejected by some Chaucerians since it was well-known that midwives in the Middle Ages inspected babies for abnormalities, and abnormalities like hermaphroditism would often result in the death of the baby. [21] However, this theory has been developed and used to create other theories like the Klinefelter syndrome theory.

The Klinefelter syndrome theory assumes that the Pardoner was born with physically normal male sex organs and therefore spared by the midwives. [22] As the Pardoner grew older, however, his genitals would become substantially smaller to eventually resemble a “geldying.” [23] The mention of the “mare” is also better supported by the Klinefelter theory. A mare refers to a female horse, implying that the Pardoner also had feminine body parts. An effect of Klinefelter syndrome is the development of female body parts like breasts, female hip bones, and female fat distribution. [24] The Eunuch Theory, on the other hand, does not explain any development of feminine body parts. If the Pardoner was simply just a eunuch, then Chaucer would have only mentioned the “geldying.” Similar to the eunuchism, characteristics of Klinefelter syndrome also include a high-pitched voice and a lack of facial or body hair which also explains the Pardoner’s “smothe” face with a “smal” “goot” voice. [25]

Skeptics of the Klinefelter Theory argue that it does not explain the Pardoner’s sexual promiscuity. After all, one of the most famous sexual innuendos in the Canterbury Tales is when the Pardoner tells the Host: “thou shalt kisse the relikes everychon.” [26] Many skeptics question how can someone with Klinefelter Syndrome be so sexually fueled. [27] However, what these skeptics fail to acknowledge is that Klinefelter Syndrome does not eliminate sexual drive. [28] Though the genitals may be smaller than normal, they are nevertheless still attached to the man and are still able to generate sexual urges. [29] The Eunuch Theory, on the other hand, is unable to explain the Pardoner’s sexual promiscuity since it claims the Pardoner’s genitals are missing altogether. In this specific area of question, the Klinefelter Syndrome trumps the Eunuch Theory in explaining the Pardoner’s sexual promiscuity.

Other scholars also argue that the Pardoner may just be trying to compensate for his lack of sexual potency. [30] The Pardoner constantly offers his “relikes” in order to substitute for his own missing parts, i.e. his testicles or his masculinity. Some scholars even discuss the numerous claims of relics that actually turned out to be fake and the important role they played in being symbols of holiness[33]. Some scholars take interest in the holiness relics symbolize and tribute it to the Pardoner’s own desire to be holy and righteous [33]. Others also argue that because abnormal bodies were shunned and isolated in the Middle Ages, the Pardoner may have bragged about his sexual promiscuity in an effort to appear normal. [31]

So Why Does This Matter?

Attempting to decipher the Pardoner’s biological sex is a long and arduous debate. The conversation has transformed from homosexuality, bisexuality, eunuchism, and now, Klinefelter Syndrome. Scholars and researchers will continue to find overlooked pieces of information in the “General Prologue,” “The Pardoner’s Prologue,” and the “Pardoner’s Tale.” Despite their differences, these scholars can all agree that the Pardoner was crafted to be sexually ambiguous. Traditional Chaucerians may reject claiming the Pardoner as queer, as a eunuch or etc. However, in all cases, there is strong evidence to suggest that Pardoner should also be analyzed outside of heteronormative lenses. People must continue to use multiple lenses of analysis in order to see the character from all angles and perspectives. Perhaps there will never be a settled debate on how the Pardoner should be sexually defined. However, what is important is that scholars and students will continue to consider a diverse variety of perspectives, debate and argue their positions, and ultimately, remind traditional academia that characters like the Pardoner are complex creations rather than standard and one-dimensional.

[1] Wilson, Jean. “Long Term Consequences of Castration in Men.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 5.6 (1999): 4324-4331.

[2] Wilson,Jean. “Long Term Consequences of Castration in Men.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 5.6 (1999): 4324-4331.

[3] Wassersug, J. Richard. “Embracing a Eunuch Identity.” Tikkun Institute Journal 4.2 (2012): 1-5.

[4] Chaucer, “The General Prologue,” The Canterbury Tales, fragment I, line 691.

[5] Curry, Walter C. “The Secret of Chaucer’s Pardoner,” Journal of English and Germanic Philology 18.2 (1919): 593–606.

[6] Murray, Jacqueline. “Introduction to the Pardoner.” Conflicted Identities and Multiple Masculinities: Men in the Medieval West, 97-106. New York: Routledge, 2011.

[7] Chaucer, “The General Prologue,” The Canterbury Tales, fragment I, lines 688-690.

[8] Cadden, Joan. The Meanings of Sex Difference in the Middle Ages: Medicine, Science, and Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

[9] Cadden, Joan. The Meanings of Sex Difference in the Middle Ages: Medicine, Science, and Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

[10] Chandler, Jed. “Eunuchs of the Grail.” In Castration and Culture in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2013.

[11] Curry, Walter C. “The Secret of Chaucer’s Pardoner,” Journal of English and Germanic Philology 18.2 (1919): 593–606.

[12] Curry, Walter C. “The Secret of Chaucer’s Pardoner,” Journal of English and Germanic Philology 18.2 (1919): 593–606.

[13] Chandler, Jed. “Eunuchs of the Grail.” In Castration and Culture in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2013.

[14] Zarins, Kim. “Intersex and the Pardoner’s Body.” Sacramento: California State University, Sacramento Press, 2010.

[15] Zarins, Kim. “Intersex and the Pardoner’s Body.” Sacramento: California State University, Sacramento Press, 2010.

[16] U.S National Library of Medicine. Klinefelter Syndrome. (2016).

[17] U.S National Library of Medicine. Klinefelter Syndrome. (2016).

[18] U.S National Library of Medicine. Klinefelter Syndrome. (2016).

[19] Netter, Frank H. “Klinefelter Syndrome Illustration.” Atlas of Human Anatomy. (2011)

[20] Rowland, Beryl. “Animal Imagery and the Pardoner.” Neophilologus 48.1 (1964): 56–60.

[21] Murray, Jacqueline. “Introduction to the Pardoner.” Conflicted Identities and Multiple Masculinities: Men in the Medieval West, 97-106. New York: Routledge, 2011.

[22] Bullough, Vern L. Medieval Masculinities and Modern Interpretations: The Problem of the Pardoner. New York: Garland, (1999).

[23] Bullough, Vern L. Medieval Masculinities and Modern Interpretations: The Problem of the Pardoner. New York: Garland, (1999).

[24] U.S National Library of Medicine. Klinefelter Syndrome. (2016).

[25] Chaucer, “The General Prologue,” The Canterbury Tales, fragment I, lines 688-690.

[26] Chaucer, “The Pardoner’s Tale,” VI 944.

[27] Rollo, David. Kiss My Relics: Hermaphroditic Fictions of the Middle Ages. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

[28] Zarins, Kim. Intersex and the Pardoner’s Body. Sacramento: California State University, Sacramento Press, 2010.

[29] U.S National Library of Medicine. Klinefelter Syndrome. (2016).

[30] Murray, Jacqueline. “Introduction to the Pardoner.” Conflicted Identities and Multiple Masculinities: Men in the Medieval West, 97-106. New York: Routledge, 2011.

[31] Murray, Jacqueline. “Introduction to the Pardoner.” Conflicted Identities and Multiple Masculinities: Men in the Medieval West, 97-106. New York: Routledge, 2011.

[32] Gold Circle Horse Racing and Setting. (2017).

[33] Dinshaw, Carolyn. “Eunuch Hermeneutics.” ELH 55, no.1 (1988): 27-51.

Behaviors of an Alcoholic

The Pardoner’s potential alcoholism is not as detailed as the topics above. However, psychological studies have been more involved when it comes to behaviors of those who rely on alcohol. A concept that can trace back to the Pardoner is one called alcoholic personality.

There are many qualities to people who are addicted to alcohol, some of which include being egocentric, grandiose, confused in sexual identity, low self-control, and being intolerant of psychological stress [1]. The Pardoner shows several examples of being a slave to the vice of alcohol.

“But first,” quod he, “heere at this alestake / I wol bothe drynke and eten of a cake” [2].

“I graunte, ywis,” quod he, “but I moot thynke/ Upon some honest thyng while that I drynke” [3].

The Pardoner belongs to the class of maintenance drinkers who may seldom appear drunk but are dependent upon alcohol to operate in a normal fashion over the course of the day. [4] Whether this reliance stems from guilt or stress, the Pardoner can’t tell his tale without having a drink. Since he is urged on to tell a moral story by the Host, perhaps the pilgrim is becoming drunk in order to think less of his other sins.

In result of this, the Pardoner involves himself within some strategies of concealment. [H]e evades responsibility for one sin by reveling in another, hiding one vice underneath the other, playing out a repertory of outrageous confessions as part of a larger rhetoric of denial and deflection necessary to an alcoholic whose true motivation remains largely a mystery to himself. [5]. Being drunk allows the Pardoner to delve more into his eccentric nature, one that claims that his relics are indeed holy.

Why Does This Matter?

Acknowledging every possibility is important to understand a character. The Pardoner does his job even with readers, deflecting anyone from seeing his greatest vice. He seems to be accepting of all of his other faults, but doesn’t acknowledge how ironic it is to drink while telling a noble story, being affiliated with the Church and advocating for selfish desires.

[1] Bowers, John M. “”Dronkenesse is Ful of Stryvyng”: Alcoholism and Ritual Violence in Chaucer’s Pardoner’s Tale.” Elh, vol. 57, no. 4, 1990, pp. 757. ProQuest. 758

[2] Chaucer, “The Pardoner’s Tale”, Canterbury Tales, Fragment VI lines 321-22

[3] Ibid. 327-28

[4]Bowers, John M. “”Dronkenesse is Ful of Stryvyng”: Alcoholism and Ritual Violence in Chaucer’s Pardoner’s Tale.” Elh, vol. 57, no. 4, 1990, pp. 757. ProQuest. 761

[5] Ibid. 762

The Pardoner and the Complexion Theory

By now, we’ve certainly established that the Pardoner is an interesting guy. But why is he the way that he is? One theory that tries to explain the Pardoner’s oddities is the complexion theory. Complexion theory dates back to the Middle Ages, and it defined a male body in terms of its complexion and bodily fluids. [1]

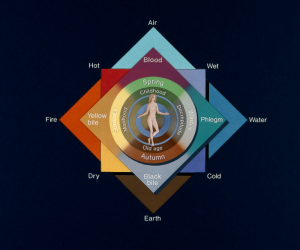

The complexion theory relies on humoral theory, which was a way of conceptualizing the workings of the human body. According to humoral theory, there are four humors, which exist as liquids in the body: blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. [2] The way that these humors interacted with each other in the body “explained differences of age, gender, emotions, and disposition.” [3] A balance between the humors was necessary to maintain a healthy body; an imbalance of humors could lead to disease and poor behavior. For example, an excess of phlegm within one’s body could result in physical and behavioral abnormalities.

A chart listing the four humors and the characteristics/elements associated with them. [2]

As seen in the chart above, phlegm is associated with wetness and coldness. This brings us back to the complexion theory. According to the complexion theory, a person with an excessive amount of phlegm in the body had a cold, clammy skin complexion. Chaucerian scholar Elspeth Whitney theorized that the Pardoner was a male phlegmatic, or a man who possessed an excess of phlegm in his body. According to medieval medicine, male phlegmatics were associated with “sexual dysfunction, lack of potency, nocturnal emissions, same-sex desire, infertility, and physical characteristics characterized as effeminate, such as soft flesh, lank, light-colored hair, inability to grow a beard, and small, hairless testicles.” [1] This description seems to fit the Pardoner well. If we look back to the Pardoner’s description in The Canterbury Tales, we can recall that the Pardoner has thin, stringy hair that is “yelow as wex” [4] and hangs stringily “as dooth a strike of flex.” [5] The Pardoner’s stringy yellow hair matches the description of a phlegmatic man. Additionally, the Pardoner is sexually ambiguous; in “The General Prologue,” the narrator states “I trowe he were a geldyng or a mare.” [6]

Furthermore, phlegmatic men were seen as “excessive, duplicitous, cowardly, and morally unstable.” [1] We don’t have to look very far for evidence of the Pardoner’s moral corruption; in fact, the Pardoner himself even boasts about his unscrupulous ventures. In “The General Prologue,” the Pardoner boasts that he is able to scam poor people out of their money using his counterfeit relics, earning more money in a day than a poor person earns in two months. According to the complexion theory, the Pardoner’s moral corruption is a result of his condition as a phlegmatic.

All of this evidence seems to fall in line with the Pardoner being a phlegmatic man, explaining his sexual ambiguity, moral corruption, effeminate behavior, and physically youthful appearance. This is one theory to consider when trying to unravel the mystery that is the Pardoner.

Why Does This Matter?

There are many theories that try to explain the Pardoner’s abnormalities, but this particular theory is rooted in medieval medicine. Using this theory to consider the Pardoner, we can think about the Pardoner through a historical lens and attempt to understand how Chaucer may have conceptualized the Pardoner, based on the medical theories and practices that existed during the Middle Ages. Furthermore, the complexion theory allows us to understand the Pardoner’s gender and sexuality without having to define him using modern labels such as “male” or “female” and “heterosexual” or “homosexual.”

[1] Whitney, “Pardoner, Complexion Theory, and Effeminacy”

[2] “Science Museum. Brought to Life: Exploring the History of Medicine.” Humours, http://broughttolife.sciencemuseum.org.uk/broughttolife/techniques/humours.

[3] “Four Humors – And There’s the Humor of It: Shakespeare and the Four Humors.” U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, 19 Sept. 2013, https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/shakespeare/fourhumors.html.

[4] Chaucer, “The Pardoner’s Tale”, Canterbury Tales, Fragment VI line 675

[5] Chaucer, “The Pardoner’s Tale”, Canterbury Tales, Fragment VI line 676

[6] Chaucer, “The Pardoner’s Tale”, Canterbury Tales, Fragment VI line 691