The Problem of Female Authority

Introduction

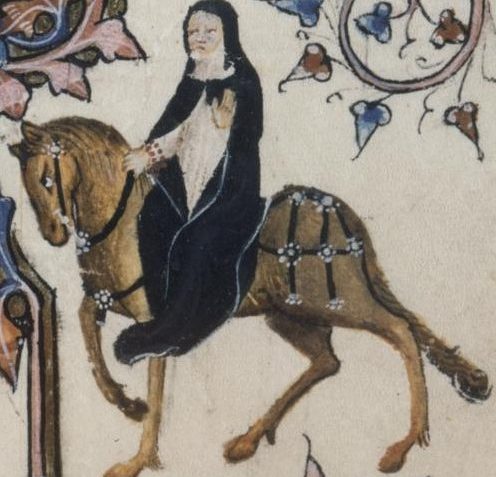

Prioresses are women who are heads of houses to an order of nuns — a powerful position for a woman. Chaucer recognizes this position of authority in “The General Prologue,” where he introduces the Prioress as fourth in his order of social hierarchy. The description of the Prioress, or Madame Eglentyne, follows the expectations of a pious and graceful woman, but Chaucer’s observations of the her jewelry and worldly fixations calls to scrutiny her faithfulness to her religious vows:

“Of smal coral aboute hir arm she bar

A peire of bedes, gauded al with grene,

And theron heng a brooch of gold ful shene,”1

The underlying question Chaucer seems to ask is “what need would a pious woman of power have of lavish jewelry or anything concerning her appearance?” This raises another interesting question regarding Chaucer’s own intentions in his depiction of the Prioress: is this a criticism of women in power or simply an addition to appearance? Contrasting the Prioress with the Second Nun offers a deeper insight:

“Another NONNE with hire hadde she,

That was hir chapeleine, and preestes thre”2

The lack of description for the Second Nun reveals Chaucer’s interest in the Prioress’ position, as the Second Nun’s position does not warrant scrutiny.

The Prioress as a Parody

Women are rarely depicted holding positions of authority and power in medieval Christendom, despite them being fairly historically common. Most positions of power that women held where under a religious background. Medieval historian Katherine J. Lewis analyzes the traditional approaches to female monasticism as she writes “the cumulative picture which emerges from these and other contemporary works of estates satire is that the essential nature of women cannot be amended by monastic vows of poverty, chastity and obedience; nuns are still governed by failings which they share with the vast majority of women”3. In other words, estate satires questioned women’s competency within the Church, commenting on their inherent fickle nature and how prone they are to experiencing lustful urges. Because of these traditional readings, women in religious positions of power such as the Prioress were likely controversial figures in literature. However, Lewis recognizes a disconnect between literary accounts and historical accounts of authoritative women in religion.

Historically, instances of immoral behavior were rare unlike what is expressed in estate satire. In fact, women with positions in religion were required to have an array of developed skills. Prioresses and abbesses in particular were elected by their fellow nuns and stood as women who bore a “dual model of leadership bearing the attributes of both authoritarianism and submission”4. Lewis makes note that one cannot attain the rank of Prioress by birthright, which contrasts with much of the statuses of the other pilgrims. A woman who is a prioress has been involved within the convent since her late teens and has risen through the ranks to eventually become elected to be their representative. This reveals, in certain instances, that status can trump gender (because the intersectionality between gender and status has not yet been considered). Being a Prioress not only exemplifies virtuous living, but also the financial well-being of her house and church events within the community.

And sikerly she was of greet desport,

And ful pleasaunt and amiable of port,

And peined hire to countrefete cheere

Of court, and been estatlich of manere5

Lewis sets out to examine the relationship between women’s gender to their positions of power and what implications that could have on the religious titles they hold. Although the Prioress’s femininity has been heavily debated, Chaucer’s stereotypes may not necessarily comment on the downfalls of her sex, but rather how gender impacts her position as an authority figure. These stereotypes can further identify what the Prioress is not, at least from a historical standpoint. It should be more valuable to move away from questioning whether or not Chaucer was misogynistic in order consider different avenues of interpreting the Prioress.

Narration as an Ironic Mockery

As Chaucer creates the description and the tale of the Prioress, he also steps into the perspective of a Prioress. Anne Laskaya, a Professor at the University of Oregon, discusses this relationship as Chaucer taking on the masquerade of the female voice6. Laskaya draws attention to how Chaucer explores feminine perspectives, electing to write in first person narration. His exploration of the female perspective leads him to tell the story of the perfect Christian boy in “The Prioress’s Tale.” Laskaya notes “it becomes quite ironic that she tells a tale about a child whose faith is so absolutely pure and simple, so unmediated by social sophistication or pretense,”7 showcasing the contrast between the “confounding” nature of Madame Eglentyne and the purity of the young Christian boy.

Thou hath this widwe hir litel sone ytaught

Oure blisful lady, Cristes moder deere,

To worshipe ay; and he forgat it naught,

For sely child wol alwey soone lere. 8

Chaucer presents the Prioress as a counterfeit nun and a counterfeit noblewoman, directing her focus onto the material world while approaching the spiritual by appearance only. What Chaucer fails to understand, however, is the intricacies of being a convent leader. The responsibilities of Prioresses involve managing the convent and, by extension, working with many people. In his efforts to mock women in positions of religious power, Chaucer unknowingly showcases the important skill of managing appearances when dealing with professional encounters regularly. The Prioress possess mastery over the mannerisms of a noblewoman and the confidence in her spirituality without having to express it outwardly. Chaucer’s masquerading as the female voice in his attempts to ridicule only offers more insight on the responsibilities and grace of these women.

Not Her Voice

The complicated narrative framework of The Canterbury Tales muddles the authenticity of the voices of the pilgrims. Chaucer the author creates a persona, Geoffrey the narrator, who reports the stories of other male pilgrims who invent stories about other women. There are only three tales that are narrated by female pilgrims, yet they are still controlled by the narration from Geoffrey. However, Anne Laskaya claims that unlike the male pilgrims who tend to mute women’s voices and separate themselves by using third-person language, Chaucer attempts to “embrace the fusion and experiments with the feminine first-person; he takes on the masquerade of the female voice.”6 The Canterbury Tales challenges the notion that women are simply obedient or rebellious. In fact, these women have the power to shape their own tales, the rules of the game, and insert their influence on the world. One way Chaucer experiments with the female voice is by allowing her ownership of her own body and authority through her words. The Second Nun’s St. Cecile protects her virginity – her source of power and autonomy – by using her words, thereby establishing a boundary around her body. She demonstrates her authority through multiple occasions of verbal confrontation against Almachius.

Laskaya suggests that the Second Nun has more authority over the Prioress and the Wife of Bath because she lacks any description. She is a disembodied voice where she cannot be subjected to interpretation. She is the “ideal woman created by absence.”9 In experimenting with the female story-telling and challenging gender stereotypes, The Prioress becomes a bit problematic because her essence is masquerade. She lies between the disembodied voice of the Second Nun and the bodied voice of the Wife of Bath. Chaucer seems to “masquerade” as the Prioress only to reinstate the gender stereotypes that women are either obedient or disobedient. Even having a present voice, the materialistic personality of the Prioress seems to undercut her authority, unlike the Second Nun. In her disobedience to her religion, her tale is qualified by the hypocrisy of being a woman and a nun as well as a Christian and a bigot. Although Chaucer reinterprets these women, their “voices” are heavily filtered. Perhaps there is an anxiety for women to express some authority.

Prioress and the Second Nun

Interestingly, while the men far outnumber the women pilgrims on the way to Canterbury, and the descriptions of the Prioress and the Wife of Bath significantly outshine the details given about of the Second Nun, Chaucer might have been indicating his own true feelings toward women and feminism through the Second Nun’s tale. The Second Nun is merely listed as being the Prioress’s “chapeleyne.”10 However, this small detail proves that she is intelligent enough to keep up a correspondence, an impressive feat during this time period since literacy was not prized as it is today. Additionally, when Chaucer was alive, literacy for the Church usually meant writing in Latin, so this was especially impressive. Even more impressive, the Second Nun is likely to become the next Prioress, an elected position. In this regard, although upper class grooming, manners, and education are helpful to being elected, piety is paramount. Even though Chaucer mocks the Prioress, he cannot escape that the other nuns must have found her worthy, and as such, he prescribes that sense of gravitas to the Second Nun.

The Second Nun’s tale features Saint Cecilia, who uses “virtue, intelligence and bravery in confronting and trouncing the evil pagan persecutor”11. Considered a radical in her time, Saint Cecilia preached. However, over time, Saint Cecilia and other radical female saints’ stories were watered down. Worse, their ability to instruct others in the rules and ways of Christianity was stripped from them during the fifteenth century. These female trailblazing saints were made to simply be examples of good Christians that followed rules and were made to appeal to both men and women. Whether it was merely subconscious or an indirect way of prescribing his own feelings, by mentioning the Second Nun in the same breath with the Prioress, Chaucer is associating the Prioress with strong women who go against the grain of what is allowed in the traditional confines of a male dominated religious organization.

1Chaucer, “General Prologue,” I.157-160.

2Chaucer, “General Prologue,” I.163-164.

3Lewis, “The Prioress and the Second Nun,” 99.

4Lewis, “The Prioress and the Second Nun,” 103.

5Chaucer, “General Prologue,” I.137-140.

6Leskaya, “Female Narrators and Masquerade,” 166.

7Leskaya, “Female Narrators and Masquerade,” 174.

8Chaucer, “The Prioress’ Tale,” VII.509-512.

9Leskaya, “Female Narrators and Masquerade,” 172.

10Chaucer, “General Prologue,” I.164.

11Lewis, “The Prioress and the Second Nun,” 112.

References:

Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Canterbury Tales, Edited by Jill Mann. New York: Penguin, 2005.

Laskaya, Anne. Chaucer’s Approach to Gender in ‘The Canterbury Tales.’ Cambridge, UK: D. S. Brewer, 1995.

Lewis, Katherine. The Prioress and the Second Nun. Edited by Stephen H. Rigby. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.