Authorial Intent

Authorial Intent

Reading The Prioress’s Tale is very strange due to the Prioress’s depiction of self and her anti-semitism; it is hard to derive what was Chaucer’s intent, or meaning, of this tale. Was this a common medieval Romance meant to demean Jews, or was Chaucer doing something more? Perhaps, “both the genre of the tale and the Prioress are satirized, as blinkered and bloody-minded.”¹. In order to attempt to gain a deeper perspective of Chaucer’s intent in the tale, the table below divides the different readings of the tale. It is important to look at the hard reading of the text because looking at a text as old as The Canterbury Tales, it is best to assess the text at face value. The soft approach allows for a more nuanced look at what Chaucer may have been subtly implying throughout the tale.

Multiple Readings of The Prioress’s Tale:

| Soft Reading: | Hard Reading: |

|

|

Beginning with the General Prologue, the Prioress is depicted satirically in order to reveal her lack of character, so her morals are put into question allowing the reader to not take the Prioress as a serious narrator. During the Prioress’s Tale, she evokes pathos in order to gain some form of authority over the narrative, however Helen Cooper notes that “the pathos tends to take over, becoming dangerously close to sentimentality.”³. Should this pathos evoked be considered dim-witted, written to show the hysterics of stories in the Miracle Romance genre? Considering the abrupt ending which condones the murder of Jews in retaliation, it is interesting to note that the Bible preaches turning the other cheek, and this common story told from the voice of a lady within the Clergy, so there is an inherent misconception or complete dismissal of one of the main ideologies of Catholicism. This could be because Chaucer, rather than satirizing the genre of romantic marvels, is raising the genre to the highest potential it could reach, which the abrupt ending of the Prioress’s Tale indicates, the murderers were murdered, absolution was achieved, but the only discernible morals of the tale were blissful ignorance, anti-semitism, and the importance of retribution in society.

The morals of stories indicate where an author’s intentions lie, what is attempted to be taught, in looking at the morals of the Prioress’s Tale, the this is brought into question because of the nature of the Prioress, who accepts her position of insignificance, stating she herself is more like an infant than a cognizant adult,

“My conning is so wayk, o blisful quene,/ For to declare thy grete worthinesse,/ That I ne may the weighte nat sustene,/ But as a child of twelf monthe old, or lesse,/That can unnethes any word expresse,/Right so fare I, and therfor I yow preye,/Gydeth my song that I shal of yow seye.”.(4)

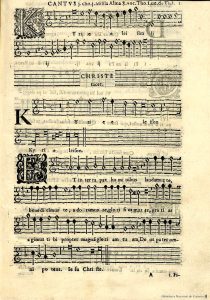

Any moral that comes from this story is derived from what children are known for, their often illogical emotion a trait the Prioress has from her depiction in the General Prologue. The Prioress’s tale of the little boy is an idealization of the childhood of a child being raised by the Church. This glorification of childhood is embodied in the main character of the story, a seven year old boy, learning the Alma Redemptoris libretto,

“This litel child, his litel book lerninge,/As he sat in the scole at his prymer,/He Alma redemptoris herde singe,/As children lerned hir antiphoner;/ And, as he dorste, he drough him ner and ner,/ And herkned ay the wordes and the note,/ Til he the firste vers coude al by rote./ Noght wiste he what this Latin was to seye,/ For he so yong and tendre was of age;/ But on a day his felaw gan he preye/ Texpounden him this song in his langage,/ Or telle him why this song was in usage;/This preyde he him to construe and declare/ Ful ofte tyme upon his knowes bare.” (5)

For those further interested in Alma Redemptoris, a video with the musical meter can be found here:https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=alma+redemptorist

The boy does not know the Alma Redemptoris because the Prioress may not know Latin. In the General Prologue she is described as speaking and understanding an English version of French, she never uses Latin aside from her necklace, which references Virgil. All of this is a dig on the Clergy by Chaucer, showing the hypocrisy displayed and inept ability to understand the language on which the church is based. As stated by Nicholas Watson, “The poem is too ironically aware of the endemic corruption in the church… to endorse an incarnational religiosity without simultaneously stripping it of its pretensions.”(6) It is not the message, but like learning an instrument, being able to match notes. The boy later learns the meaning of the song, described to him in his native language, which is presumably English, although this story takes place in Asia. The libretto in English is,

“Sweet Mother of the Redeemer, the passage to the heavens,/the gate of the spirits of the dead, and the star of the sea, aid the falling./Mother of Him who cares for the people: you who brought forth/the wonder of Nature, your Creator./ Virgin before and after, who received of Gabriel/ with joyful greeting, have pity on us sinners.”(7)

The story, told by the Prioress shows that she is more interested, as most children are, in the motherly and forgiving figure of the Virgin Mary rather than support the more stringent Old Testament perception of forgiveness. The nature of this song is eulogistic, and the boy, who now understands the song, goes about the city singing the song. The romance soon hits a peak and Jews of the neighboring Ghetto cut the boys neck to the bone. The boy miraculously continues singing the Alma Redemptoris, dies, and the last stanza of the tale is not the boy being buried in a lavish tomb, but in the murder of the Jews because of a brief respite from self control,

“O yonge Hugh of Lincoln, slayn also/With cursed Iewes, as it is notable,/ For it nis but a litel whyle ago;/Preye eek for us, we sinful folk unstable,/That, of his mercy, god so merciable/ On us his grete mercy multiplye,/ For reverence of his moder Marye. Amen.”(8)

Once again the Prioress uses the forgiving Virgin Mary to appeal for forgiveness of these extremely violent murders, assuming that God is ‘merciable’ and therefore breaking many of the ten commandments in the last stanza is justified. If Chaucer is not satirizing the story, then these views on Christianity are very scattered. On the one hand, he holds contempt for people who pretend to have deep faith, but conversely, he endorses martyrdom and the belief of God forgiving what is described as a justified murder through the voice of the Prioress. As Ann Laskaya notes, the Prioress is more complex than most of the other narrators of the Tales, she has a true intersectional personality being a ‘conglomerate’ of a ‘nun’ and ‘lady’.(9) Her perception of the mercy of god comes through her own fascinations as a lady, which is often bloody minded, while abhorring the real sight of violence. Her complexities, like Chaucer, often are discovered in her juxtaposed beliefs. Helen Cooper notes that the genre that is being used to villainize Jews, while not answering any moral code, “easy anti-semitism may be normal for the genre, there is a complacency that ignores all hard questions rasied elsewhere about evil.”(10).

While Chaucer did mock the Clergy throughout the Prioress’s Tale, his anti-semitic views are put on full display by the end of the novel. This is problematic for modernist readers of the tale. These readers are bound to derive a more moral message from this tale because it is difficult to accept that a text as revered as The Canterbury Tales, has anti-semitic morals riddled with toxic masculinity throughout the Prioress’s Tale. While hard to accept, the readers get a clearer understanding of the roots of anti-semitism in Europe, something that the setting of the story argues is a worldly topic. It is not easy to discover true intentions, but through looking at the morals Chaucer reveals and the narrator he chose to tell the tale, two separate themes appear; Jews will murder singing Christian children, and it is okay to subsequently murder those Jews. Through the depiction of the Prioress’s hypocrisy, Chaucer is condemning all of the Clergy for using their positions to gain material goods, while ignoring the more important religious devotion required of all Christians. The Prioress is mocked through her choice of genre, showing that only superficial women like these Romances, but if the story was told through a more respectable narrator, namely a man, an anti-semitic theme would still appear. The anti-semitism is not connected to the Prioress’s hysterics, but is a commonly held belief, Chaucer is showing even the Prioress, as dim witted as she is, feels the same way. The intent Chaucer had while crafting the Prioress’s Tale was to show the weak cunning of a woman of the cloth, as well as to sensationalize the murder of a boy in order to further villainize Jews.

For further information on Anti-Semitism, please refer to the section under the Prioress with that title.

Footnotes

-

- Bale, Anthony. “‘A maner Latyn corrupt’: Chaucer and the Absent Religions.” In Chaucer andReligion. Edited by Helen Phillips, 52–64. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2010.

- Cooper, Helen. The Structure of the Canterbury Tales. Athens: The University of Georgia Press,

- “Links within Fragments: Fragment VII(B2): The Tales of the Shipman,

the Prioress, Chaucer, the Monk and the Nun’s Priest”

- Cooper, Helen. The Structure of the Canterbury Tales. Athens: The University of Georgia Press,

- “Links within Fragments: Fragment VII(B2): The Tales of the Shipman,

the Prioress, Chaucer, the Monk and the Nun’s Priest”

- Chaucer, Geoffrey, -1400. (1948). The Canterbury tales of Geoffrey Chaucer; a new modern English prose translation by R.M. Lumiansky II. 1671-77.

- Chaucer, Geoffrey, -1400. (1948). The Canterbury tales of Geoffrey Chaucer; a new modern English prose translation by R.M. Lumiansky II. 1707-1719.

- Watson, Nicholas. “Christian Ideologies.” In A Companion to Chaucer. Edited by Peter Brown,75–89. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

- Green, Aaron. “Alma Redemptoris Mater Lyrics and Translation” https://www.thoughtco.com/alma-redemptoris-mater-lyrics-724386

- Chaucer, Geoffrey, -1400. (1948). The Canterbury tales of Geoffrey Chaucer; a new modern English prose translation by R.M. Lumiansky II. 1875-80.

- Laskaya, Anne. “Female Narrators and Chaucer’s Masquerade: the Second Nun, the Prioress and the Wife of Bath.” In Chaucer’s Approach to Gender in The Canterbury Tales. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 1995.

- Cooper, Helen. The Structure of the Canterbury Tales. Athens: The University of Georgia Press,

- “Links within Fragments: Fragment VII(B2): The Tales of the Shipman,

the Prioress, Chaucer, the Monk and the Nun’s Priest”