Wifehood

Legal Expectations of Medieval Marriage

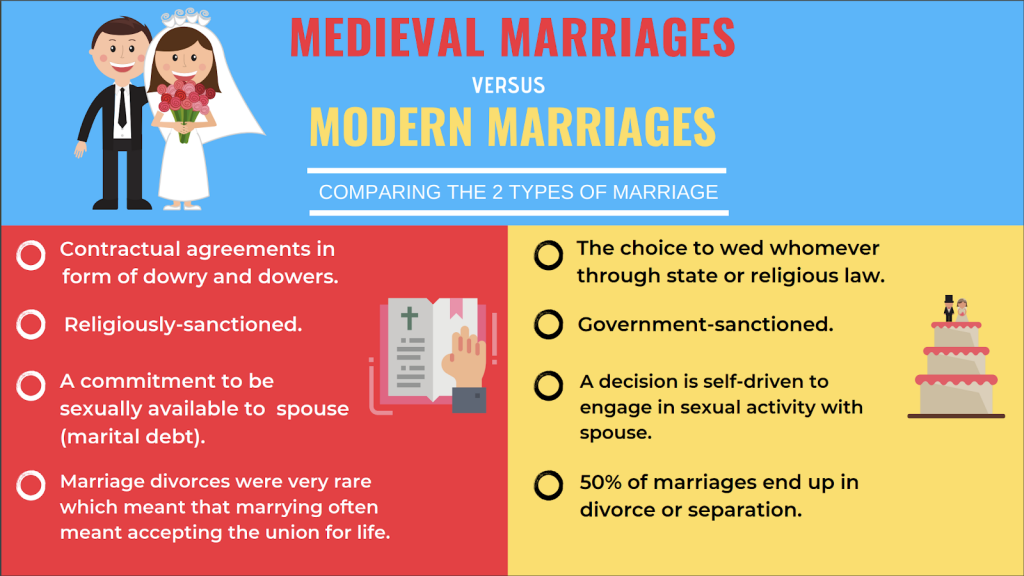

The Wife of Bath was married five times which raises the question of how marriages were established in the Middle Ages. In medieval times, marriage was a contractual agreement, meaning both parties, the man and the woman, contributed their resources or assets to the union of both families in the form of a dowry or dower:1

Marriages, for the most part, were arranged and based on properties and goods which meant that potential candidates for marriage were determined based on their assets; however, that is not to say that all marriages were loveless. 4 For women, unions often brought the security of resources which they became legally responsible for if their husbands died.

Marriage for women also meant a shift in their legal name from “daughter of” her father to “wife of” her husband. 5

Additionally, marital expectations included a commitment to be sexually available to their spouse, referred to as the “marital debt.” 6 While both husband and wife entered their union, it was not necessarily an equal one. Once married, women became the husband’s legal property and were typically confined to his household.7

Traditionally, the role of a wife in marriage was to preserve her virtue and show obedience to her husband, and the husband was to provide for the wife. Marriages did not always follow this ideal. There were unhappy marriages and domestic violence involved in some cases. Medieval divorces were rare, which meant that marrying often meant accepting the union for life. The Church dealt with divorces, but it was more interested in keeping unions together rather than separating them.8 However, there were instances where the Church allowed for divorce or annulment. This typically occurred in the rare cases that the marriage was nonconsensual or incestuous, if one partner lived in fear of their spouse, or sometimes if the spouse was impotent.9

The Wife of Bath’s Marriages

With medieval marriage in mind, how does the Wife of Bath fit into all of this? First, the Wife of Bath begins her prologue by speaking about her experience and expertise as a wife; she was first married at the age of twelve and experienced four other marriages after the first husband died.10 Her desire to remarry is partially based on the “marital debt.”

“Myn housbonde shal it have bothe eve and morwe,

Whan that hym list come forth and paye his dette.“11

The Wife here refers to the debt of sexual obligations in marriage. She is describing her husband’s debt to her while also subverting her dominance over her husband and defying the role of women being obedient to their husband.

(For more on wifely disobedience, see section on female dominance)

The Wife of Bath’s first three husbands were old and wealthy12. Since marriage formations were based on assets and wealth, it is no surprise that her first three husbands had wealth and properties. As stated by the Wife of Bath:

“They had me yeven hir lond and hir tresoor;

Me neded nat do lenger diligence.“ 13

Her husband’s land and fortune depict the shared assets and land the Wife of Bath gained control of as part of her marriage.

Moreover, marriages in the Middle Ages were grounded in status and wealth. Marrying benefitted women because they allocated wealth and in some cases inheritance from their husbands.14However, marriage also was complicated. Wives were under the legal control of their husbands and therefore limited in their agency.

Because of this, the Wife of Bath showcases both the ills and benefits of marriage in medieval times.

1Hanawalt, Wealth of Wives, 69.

2Hanawalt, Wealth of Wives, 70.

3Hanawalt, Wealth of Wives, 70.

4Hanawalt, Wealth of Wives, 118.

5Hanawalt, Wealth of Wives, 70.

6Hanawalt, Wealth of Wives, 118.

7Hanawalt, Wealth of Wives, 118.

8Hanawalt, Wealth of Wives, 128.

9Hanawalt, Wealth of Wives, 128.

10Chaucer, “The Wife of Bath Prologue,” III.3-6.

11Chaucer, “The Wife of Bath Prologue,” III.152-3.

12Chaucer, “The Wife of Bath Prologue,” III.197.

13Chaucer, “The Wife of Bath Prologue,” III.204-5.

14Hanawalt, Wealth of Wives, 120.

References:

Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Canterbury Tales, “The Wife of Bath’s Prologue.” Edited by Jill Mann, Penguin Books Ltd, 2005.

Hanawalt, Barbara A. The Wealth of Wives:Women, Law, and Economy in Late Medieval London. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007.