Women on Top

Empowerment or Ridicule?

The Wife of Bath’s Sexual Agency

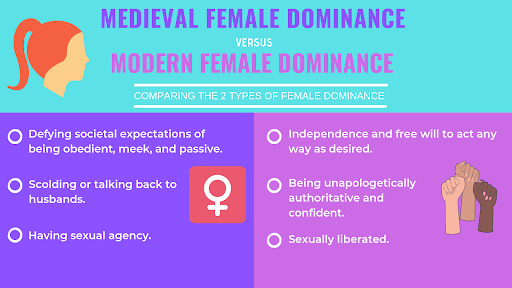

The Wife of Bath, or Alisoun, is an unconventional woman who rejects the societal expectations of men, which typically demanded wives to be obedient and sexually pure. “The Wife of Bath’s Prologue” demonstrates how Alisoun scolds and curses her husbands, which are ways that she asserts her dominance over them as a woman on top figure who defies misogynistic expectations. She advises women to do the same if they want to be a “wys wyf”:1

“Now herkneth hou I baar me proprely,

Ye wise wyves, that kan understonde.

Thus shulde ye speke and bere hem wrong on honde“2

The long tirade between lines 234-256 follows this advice and consists of various insults that she throws towards her husbands, like “olde kaynard,” “olde lecchour,” or “olde fool.“3 The rest of the prologue is sprinkled with insults similar to these. She also curses her husbands with declarations such as:

“With wilde thonder-dynt and firy levene

Moote thy welked nekke be tobroke!”4

These examples show how she would treat her husbands as inferiors, rather than allowing them to control her as society expected.

(For more on the ways the Wife of Bath rejects conventional marriage expectations, see the section on wifehood)

The medieval church seriously disdained, and even punished, women who would scold and curse their husbands.5 The “scolding wife” even became a stereotype, and many people, especially in the Church, would ridicule these women.6 Therefore, even though the Wife of Bath epitomizes the empowered woman on top figure, medievalist Ruth Mazo Karras points out that Chaucer may have shown her excessive scolding to ridicule her as the “scolding wife” stereotype.7 Therefore, as a woman who refuses to be meek and obedient, she is simultaneously fighting against misogyny while also fitting the stereotypes that misogynists criticized and warned men against.8

The Wife of Bath’s sexual experiences also portray her as a woman on top because she often asserts her sexual superiority over men:

“An housbonde I wol have — I wol nat lette —

Which shal be bothe my dettour and my thral,

I have the power durynge al my lyf

Upon his propre body, and noght he.“9

Here, she refers to her husband as a debtor and a slave, which indicates how she expects sex from her husbands for her own pleasure. Typically, men in the Middle Ages would have expressed these sentiments and it was rare for a woman to display this kind of dominance. When she states that she holds the power over the man, “and noght he,” she represents the woman on top figure.

“The Mounted Aristotle“

These expressions of sexual superiority portray the Wife of Bath as the woman in the widely circulated medieval image of the “mounted Aristotle,” which was an image of the philosopher Aristotle on all fours with a woman sitting on his back.10 The woman in the image is typically holding a whip, implying that the man underneath her is at her mercy.11 This image demonstrates feminine sexual agency and power, and a rejection of the Church’s guidelines about sex: that is, that a husband should be on top of his wife in order for sex to not be sinful.12

An even more specific connection between Alisoun and the figure of the “mounted Aristotle” is when she states,

“…tribulacioun in mariage,

Of which I am expert in al min age–

This is to seyn, myself have been the whippe” 13

In this excerpt, the image she evokes of herself brandishing a whip directly mirrors the “mounted Aristotle” figure. Therefore, by scolding her husbands and demonstrating her sexual dominance, the Wife of Bath seems to be a representation of the woman on top in the “mounted Aristotle.” In accordance with medieval law at the time that allowed men to “correct” their wives’ behavior through physical punishment,14 the Wife of Bath ends up being abused by her fifth husband, Jankyn.15 One could interpret that this is a result of Alisoun’s assertion of sexual dominance over men.

This brings Chaucerians to the ever-circulating question: was Chaucer a sort of proto-feminist who used the Wife of Bath’s erotic agency to demonstrate the possibilities of female power, or did he want to show that this kind of female agency must be corrected?

Marriage and Dominance

The Wife of Bath is a dominant figure within all of her marriages. Through the way she presents herself in her prologue and tale, it is easy to see that she craves dominance and choice. In her prologue, she goes through her marriage history and even admits to using sex as a way to control her husbands.16 She is representative of a new emergence, or a hope for a new emergence, of women who gained more power given the new social circumstances of the Middle Ages and the rise of the middle class. Because she is a textile worker,17 she is able to gain some semblance of independence in her life. Although it was not uncommon for women during this time to gain some wealth in their work, the Wife is not a historically accurate example of the average secular woman. She takes on the role of dominance because of her wealth and inherited property.

Because of this unconventional dominance, medievalist Glenn Burger argues that the Wife of Bath takes on what he calls “female masculinity.”18 He writes that she has a sort of “female masculinity that shows us the construction of dominant masculinity without reinscribing the male bodies in which such masculine power traditionally inheres.”19 Through this performative masculinity, she reinforces the idea that masculinity is inherently dominant, but instead of tying it to the male body, she instead shows how it can be used by women as well. This embodiment of masculinity shows the way the Wife, who at time seems to be a proto-feminist and other times an anti-feminist, embraces the gendered world that society has established.

The fact is, the Wife is both and neither a proto-feminist nor an anti-feminist because the idea of feminism wasn’t even conceived in Chaucer’s time.

The Wife indisputably takes on a more dominant masculine role, but she still works within the confines of her gender. Medievalist Alcuin Blamires points out that historically “a wife was supposed to ‘conserve’ her husband’s goods on his behalf just as she conserved her body on his behalf.”20 The Wife does not stay home; as a pilgrim, she is introduced right away as a wanderer. Not only does she wander about on many pilgrimages to Jerusalem, Rome, Galicia, and Cologne, 21 but she also has a wandering eye. She is always looking for her next husband in case her current one should die.22 She learns how to gain the dominant position with her first four husbands through nagging, manipulation, and lying,23 but her fifth husband, Jankyn, is not so easily controlled. He resorts to physical violence in order to get his way.24

All of this illustrates the Wife of Bath as an empowered woman who takes what she wants, but the only way she is be able to get what she wants is through marriage to a man.

Female Intervention in “The Wife of Bath’s Tale“

The Wife of Bath’s tale is interesting because after reading her prologue, it almost seems like a tale she would not tell. Here’s a quick summary of the details relevant to female intervention and control:

At the very beginning of the story, we are introduced to a protagonist: an Arthurian Knight who rapes a young woman. The young woman is not visited again in the story, instead, we follow the knight. He is supposed to be sentenced to die when the unnamed Queen, presumably Arthur’s Guinevere, intervenes and takes his fate into her own hands. She gives him a year and one day to find out what women want most and if he cannot find the answer then he is to die. He goes around asking but it isn’t until he comes across an old woman that she gives him the answer to save his life in exchange for a later favor. The knight is able to win his life with her answer, but is stuck having to marry the old woman as compensation. One night she asks him to choose if he’d rather have a young beautiful wife or a loyal wife. Resigning to indifference, the knight allows her to choose for herself. When he grants her that choice, she becomes a loyal, beautiful wife and the tale ends in a sort of happily ever after.25

Both the old woman and the unnamed Queen (Guinevere) are credited with saving the knight’s life. Medievalist Elizabeth Scala suggests that because of this, “The Wife of Bath’s Tale” is “a world improved by the ministrations of women.”26 The world is a better place because of the fact that women interfere in the knight’s sentencing and are able to reform him. Anne Laskaya takes this argument a step further, stating that “the ‘female’ narrators create main characters who, through words, rather than silence, assert considerable influence on the world, and that influence is positive.”27 The women are able to challenge the males within the story and this sets the stage for more gender equality within marriages.

On the other hand, the Queen has the power to decide only because her King allows it, and the old woman gains control because the knight gives her the power. As Scala points out, “the old woman in the Wife’s Tale must clarify the power she has gained from the knight … Her control in this situation is actually self-control, the ability to “chese” herself over and against the privilege marriage affords to men.”Thus, the women in the tale have mastery over themselves, but their husbands maintain sovereignty. Scala then argues that this tale is one that is essentially a “how to” on gaining a happy husband.28

The tale ends with the knight gaining happiness despite the fact that he does not deserve it. Even if this is true, Laskaya argues that the tale is symbolic of the Wife’s hopes for change. The Wife tells her tale in her own present time set in the past with visions of the future. She can “imagine a different world … The utopian fairy world exists in the imagination; and in the mind that can imagine the folktale, the old crone can also be the young maid.”29 The Wife welcomes change and in fact yearns for it. The tale is about more

1Chaucer, ‘The Wife of Bath’s Prologue,” III.231.

2Chaucer, ‘The Wife of Bath’s Prologue,” III.224-26. For modern translation, see https://sites.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/teachslf/wbt-par.htm.

3Chaucer, ‘The Wife of Bath’s Prologue,” III.235, III.242, III.357.

4Chaucer, ‘The Wife of Bath’s Prologue,” III.276-277. For modern translation, see https://sites.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/teachslf/wbt-par.htm.

5Karras, “The Wife of Bath,” 328.

6Karras, “The Wife of Bath,” 329.

7Karras, “The Wife of Bath,” 29.

8Alcuin Blamires, The Case for Women in Medieval Culture, quoted in Ruth Mazo Karras, “The Wife of Bath,” 329.

9Chaucer, ‘The Wife of Bath’s Prologue,” III.154-59.For modern translation, see https://sites.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/teachslf/wbt-par.htm.

10Desmond, “Sexual Difference,” 15.

11Desmond, “Sexual Difference,” 22.

12Desmond, “Sexual Difference,” 18-19.

13Chaucer, ‘The Wife of Bath’s Prologue,” III.173-75. For modern translation see, https://sites.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/teachslf/wbt-par.htm.

14Desmond, “Sexual Difference,” 32.

15Chaucer, ‘The Wife of Bath’s Prologue,” III.795.

16Chaucer, ‘The Wife of Bath’s Prologue,” III.407-11.

17Chaucer, ‘The General Prologue,” III.447.

18Burger, Chaucer’s Queer Nation. 79.

19Burger, Chaucer’s Queer Nation. 95.

20Blamires, Alcuin.“Liberality…” 135.

21Chaucer, ‘The General Prologue,” III.463-66

22Chaucer, ‘The Wife of Bath’s Prologue,” III.568-73

23Chaucer, ‘The Wife of Bath’s Prologue,” III.234-56.

24Chaucer, ‘The Wife of Bath’s Prologue,” III.795.

25Chaucer, ‘The Wife of Bath’s Tale,” III.857-1264.

26Scala, Desire in the Canterbury Tales. 131.

27Laskaya, Chaucer’s Approach to Gender. 167.

28Scala, Desire in the Canterbury Tales. 139-40.

29Chaucer, ‘The Wife of Bath’s Tale,” III.857-1264.

References:

Burger, Glenn. Chaucer’s Queer Nation. University of Minnesota Press, 2003.

Blamires, Alcuin. “Liberality: ‘The Wife of Bath’s Prologue’ and ‘Tale’ and ‘The Franklin’s Tale’.”

Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Canterbury Tales, “The Wife of Bath’s Prologue.” Edited by Jill Mann, Penguin Books Ltd, 2005.

Desmond, Marilynn. Ovid’s Art and the Wife of Bath: The Ethics of Erotic Violence. Ithaca:

Cornell University Press, 2006.

Karras, Ruth Mazo. “The Wife of Bath.” In Historians on Chaucer: The ‘General Prologue to the

Canterbury Tales. Edited by Stephen H. Rigby, with the assistance of Alastair J. Minnis,

319–33. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Laskaya, Anne. Chaucer’s Approach to Gender in the Canterbury Tales. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1995.

Scala, Elizabeth. Desire in the Canterbury Tales. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2015.