The Female Imagery

Christ the Mother

Chaucer seems to reinforce the traditional readings of the estate satires which depicts the Prioress as hypocritical, vain, and lustful – inherent characteristics for the female sex. However, according to Caroline Walker Bynum, female and male religious writers use gender-related ideologies differently which are not necessarily misogynistic in either application. She notes that men are more preoccupied with the definition of “the female” and focus more on conversion while women tend not to use opposing gender images and focus more on internal motivation and emphasis on the self. She claims that “it is men who develop conceptions of gender, whereas women develop conceptions of humanity.”1 Male writers tend to link their own “motherhood”, or ability to nurture with that of the sacrifices of Christ on the cross as well as their uncertainty to “fatherly” discipline to the authority of the clergy. Women writers did not associate motherhood with nurturing as often nor did they use motherhood and fatherhood as contradictory descriptions.

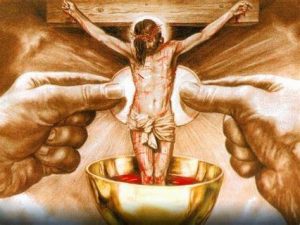

Marguerite of Oingt spoke of Jesus in terms of a mother but referred to “motherhood” as a metaphor for Christ’s suffering on the cross. She states, “When the hour of your delivery came you were placed on the hard bed of the cross… it is no surprise that your veins burst when in one day you gave birth to the whole world.”2 Jesus metaphorically gives birth to the world which equates motherhood to Christians sustaining off the blood and flesh of Christ and the sanctity of suffering.

Bynum compares interpretations of images of the soul where men tended to associate “femaleness” with meekness and a disassociation from earthly pleasures. Since men characterized religious women to lead more violent self-disciplined lives, men sought conversion of the male to female to renounce the world. However, women did not have binary biases separating the two sexes. In fact, they often mixed female and male images when concerning the soul. Bynum includes an example of Hadewijch of Antwerp where she likens the soul to “a knight seeking his lady” and “a bride reaching her lover.”3 Unlike the male writer who sought renunciation and reversal, the female writer did not express renunciation in the mixed images of the knight or bride. Women did seek to elevate themselves from the world and renounced earthly possessions such as jewelry and makeup. However, they still spoke of their relationship to Christ still using the stereotypical female roles and behaviors. Instead of reversing their gender, they committed fully into it in order to elevate their union with Jesus.

Considering the Prioress’s position of authority, her sex should not only render her meek or submissive. She should be recognized as female authority figure. According to Bynnum and the female interpretations of the female body, the Prioress should be a recognized authoritative figure becuase motherhood was also associated to discipline. While religious men were uncertain of the authoritative powers of the clergy and sought to become more “womanly”, or less authoritative, the Prioress should be able to lean into her position as a woman of power. To leaning in to her gender meant to also accentuate her femininity, thereby strengthening her marriage with Christ.

According to Caroline Walker Bynum in “The Female Body and Religious Practice in the Later Middle Ages,” male and female were speculated within the dichotomous terms of “intellect/body, active/passive, rational/irrational, reason/emotion, self-control/lust, judgment/mercy and order/disorder” [4] respectively. Thus women were viewed under misogynistic lens. In this case, the misogynistic notions were shaped by the fact that male authorships believed the Virgin Mary as the dominant symbol of female chastity[5]. Therefore, male authors use Mary as a model for women. For instance, the Virgin Mary becomes the symbol and motif in the “Prioress’ Tale”:

Wherfore I singe, and singe moot, certein,

In honour of that blisful maiden free, […]

And after that, thus said she to me:

“My litel child, now wol I fecche thee

Whan that the grein is fro thy tonge ytake.

Be nat agast; I wol thee nat forsake.[6]

In other words, the boy in the “Prioress’ Tale” is able to sing despite being dead and his throat cut cruelly because it is the Virgin Mary who will save him from his misery. Thus the Prioress’ tale is considered a “miracle of the Virgin.” Regarding this, Chaucer uses the image and symbol of the Virgin Mary as an admiration and motivation for the boy to express his strong devotion to Christianity. The little boy’s devotion then leads him to be saved by Virgin Mary. Likewise, it implies that because the Prioress also believes in the Virgin Mary, she too, wants to be saved from some kind of miracle. But saved from what? Saved from being a nun, being unable to practice being a courtly, noble woman? Saved from her blind devotion to Christianity? Therefore, as a nun, the Prioress herself is expected to possess chastity. Yet her characterization is implied that she engages in the act of courtly manner and courtly love. The Prioress uses the image of the Virgin Mary to justify her own devotion to Christianity, to hint at her own chastity, yet ironically, the Prioress is characterized as a satire by Chaucer because she is the opposite of a devoted nun to Christianity. Therefore, is Chaucer satirizing the Prioress’ devotion to the Virgin Mary because her characterization is the opposite of being chaste, at least is what is implied through her affinity or desire to be a courtly lady and courtly love.

Furthermore, Bynum points out that the female soul is seen as childlike. In relation to this, the Prioress does tell the audience that she will tell the tale in the manner of a child:

My konning is so waik, o blisful queene,

For to declare thy grete worthinesse,

That I ne may the weighte nat sustene,

But as a child of twelf-month old or lesse,

That kan unnethes any work expresse,

Right so fare I; and therefore I yow preye,

Gideth my song that I shal of yow seye.[7]

According to Bynum, male writers saw the female soul as “”childlike” or “womanly” dependence of the good Christian on a powerful, “fatherly” God”[8]. In other words, by having the Prioress assume the intelligence of a child is the same way as undermining her intellect towards the moral of the story and most importantly her Christian devotion and relationship to God. By doing so, male writers challenge the fact that women are indeed weak and that to truly become a woman is to renunciate and convert[9]. Considering this, it is because men wanted assume the role women through their text, to seem weak and become strong by renunciation and conversion[10], to die in order to live. Likewise, the boy dies because of the underlying anti-semitic factors within the text, but to reveal that the boy’s life will be saved in heaven through the miracle of the Virgin Mary. Further, male writers sought to to become ordinary to extraordinary [11]through the reversal of gender roles. In this way, Chaucer ridicules the fact that men use women in appropriating their identity in order to transcend the other sex.

[1] Bynum, Fragmentation and Redemption, 156

[2] Bynum, Fragmentation and Redemption, 162-63

[3] Bynum, Fragmentation and Redemption, 171

[4] Bynum page 151

[5] Bynum page 152

[6] Canterbury Tales “The Prioress’s Tale” lines 663-669

[7] Canterbury Tales “The Prioress’s Tale” lines 481-487

[8] Bynum page 165

[9] Bynum page 166

[10] Bynum page 166

[11] Bynum page 165-166