Romance and Sexuality

Reclaiming Power through Love and Sexuality

In the Wife of Bath’s prologue, she establishes herself not just as a experienced wife (as her name suggests), but also as a romantic. She states:

“For, God so wysly be my savacioun,

I loved nevere by no discrecioun,

But evere folowed I min appetit,

Al were he short, or long, or blak, or whit.

I took no kepe, so that he liked me.”1

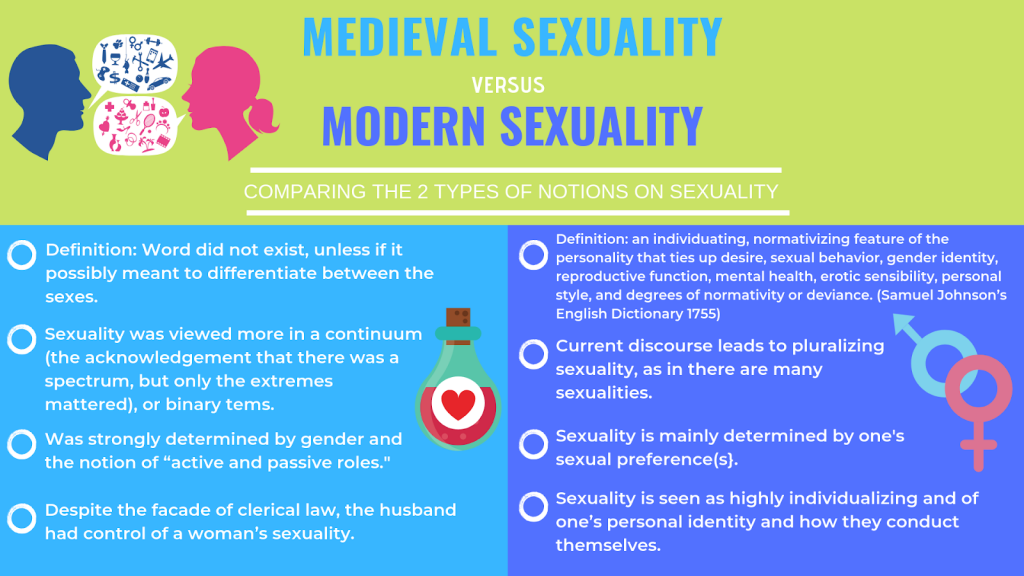

Such ideas as love and romance within the realm of marriage were uncommon in medieval society. In reading the Wife of Bath through a contemporary lens, terms like love and sexuality are often used to describe the overtly sexual nature of her being as well as describing her amorous boldness; however, such terms did not have the same meaning they do today, nor were they solidified in their meanings. There existed a “wide semantic range of the word ‘love’” specifically in the works of Chaucer, ranging from religious to sexual meanings2, and “not even in Chaucer did the language of courtliness translate in its full semantic range into English.”3 In terms of sexuality, “no such word existed until quite recently.”4 “Chaucer knew no word for, and to that extent possibly had no emphatic concept of, ‘sexuality’ – as distinct from, say, ‘difference in sex’-whether in vernacular English and French, or in Latin.”5 With this in mind, I will now continue to explore the implications of what merging the “tensions between physical and spiritual love”6 could mean for the Wife of Bath’s role in challenging societal norm in the middle ages.

First, it is important to establish that the Wife of Bath is empowering in terms of female sexuality alone, and not necessarily all forms of queerness. This is because she works within the realm of heteronormativity through the institution of marriage, utilizing church laws to her advantage. This is “what theologians had done for centuries:7“ enforcing the laws of marital debt disproportionately on women due to the fact that “husbands [had] considerable latitude in deciding when it is necessary for a wife to receive her ‘debt.’”8 This debt refers to the sexual contract between man and wife. In fact, wives were expected to “be too modest to ‘seek’ the husband’s ‘payment’” and the husband would “render the ‘payment’ even if it were not specifically being asked for.”9

(For more on “marriage debt,” see section on wifehood)

The Wife of Bath also reclaims her power as a woman by entwining notions of religious and secular love into one, and embedding that within the relationship of marriage. She does so by utilizing the term love in a religious context, superficially meaning the spiritual sense, but actually using it in the physical sense to argue that husbands must pay their wives’ marriage debt.

“Right thus th’Apostle tolde it unto me,

And bad our husbondes for to love us wel;

Al this sentence me liketh everydel”10

The Wife’s decision to remarry may sound counterintuitive, but in comparison to married women and single, unmarried women, widowed women in the Middle Ages exercised considerable social and economic power. In addition to controlling property they inherited from their late husbands, they took a more active role in courtship due to the fact that they often had many interested suitors.11 Why struggle within the system of marriage when she had more freedom as a widow? Despite these perks, (I say this with caution to be clear that such privileges did not entail more rights or equality by any means) there was one crucial thing denied to widows and unmarried persons alike. That’s right, sex. The Wife of Bath mentions in her prologue that she loves her fifth husband best despite him being physically abusive because he is good in bed.

“That thogh he hadde me bet on every bon,

He koude winne again my love anon.

I trowe I loved him best, for that he

Was of his love dangerous to me.”12

Here she uses the term love in multiple ways: one way is to describe her emotions towards her fifth husband, and the other to describe him as a good lover in bed. Although bold in expressing her sexual desires, she makes sure to embed such language within the notions of love as a way of validating it, because her expression of independent sexual desire would not be well received. This can also be seen when she argues that genitals were made for sex:

“In wifhode wol I use min instrument

As frely as my makere hath it sent.”13

In this case, she uses the same tactic of embedding her sexual desires within an acceptable form, in this case marriage.

Heteronormativity and Queerness

It is notable that the Wife of Bath is very successful in swaying her audience. This is in part due to the fact that she works within societal norms and subverts certain structures that are made to suppress women. She accomplishes this through her understanding of the male dominated structures and the men who dominate them. Her tactics starkly contrast some of the other pilgrims, particularly the Pardoner, who actually interjects during her prologue. As a result, a tension exists between the two and the ways they both present queerness and challenging convention; The Wife of Bath works within heteronormativity, while the Pardoner seemingly rejects it.14 The Pardoner is the first to call her out on her preaching, whether in spite or not is subject to interpretation. He points out her blatant subversion after she clearly states in the beginning of her prologue that she had, “noon auctoritee” 15by exclaiming, “‘Now, dame, by God and by Seint John,/ye been a noble precher in this cas!” 16In addition to the Wife of Bath reclaiming power by speaking like a religious authority, she also subverts traditional religious ideas by taking the stance of a new religious movement called lollardy (or at least pulling out the points that work to her advantage). Lollardy was a religious movement that challenged Orthodox Christianity. One of the many lollardy claims was that women were naturally promiscuous, and therefore must be married in order to control their sexual perversions.17 It is through this notion that the Wife of Bath is able to claim her overt sexuality, and advocate for it under the guise of religion.

It is no secret that the Wife of Bath herself is rebellious character that challenges societal norms. What is most remarkable about her, however, is not limited to her manipulation within a patriarchal system to get what she wants, but rather that her ideas (even if unwittingly) pave the way to more radical notions that extend beyond her heteronormative outlook. Even if only in marriage, establishing love and sexuality to be impending human forces sets a precedent for more than just heterosexual women. After all, if religion was able to change and adjust to accommodate for women’s “perversions”, what other “perversions” can utilize the same course of logic that the Wife of Bath used to their own advantage?

This idea of romantic love, a love that encompasses emotional, spiritual, and physical aspects, leads to narratives that portray two people who cannot deny their attraction to each other and must be together at all costs. The Wife of Bath may use romance as a way of pushing heteronormativity,18 but other forms of queerness are also able claim a space through her championing of love and sexuality. A homosexual plot can easily disrupt a heteronormative view of romance.19 Whereas in a traditional romance, a dragon or a duel is what keeps lovers apart, in the name of love, it could be social boundaries that act as the challenge to overcome.

In conclusion, even if a term did not exist to describe the Wife of Bath’s subjectivity at the time, her ideas, personality, and character overall helped develop and establish ideas of sexuality and solidify the idea of love into the all encompassing word it means today, and potentially opened a path for other “perversions” to reclaim power.

The Wife of Bath as a Romantic

The tale that the Wife of Bath tells following her sex and marriage filled prologue seems to contradict some of the attitudes the Wife presents. As medievalist Helen Cooper suggests, readers may expect a fabliau– a raunchy comedy that typically involves cuckolding –to follow “The Wife of Bath’s Prologue” due to her own raunchiness and unashamed vulgarity.20 But not so. “The Wife of Bath’s Tale,” rather, is an Arthurian romance filled with underlying discourse about morality and women’s subjection to men. These deeper themes are particularly evident in the “loathly lady’s” “hundred-line discourse…on the inward nature of true nobility and the value of poverty”21

“Looke who that is moost vertuous alway,

Privee and apert, and moost entendeth ay

To do the gentil dedes that he kan,

Taak him for the gretteste gentil man“22

This meditation on the true nature of morality seems to reveal that the Wife is an idealist, even after what appears to be a scandalous prologue. Another major aspect of this is the happily ever after at the end of her tale. 23

But how did we get here?

(For a summary of the tale, see Women on Top page)

Given the fact that the knight who lives married happily ever after to a beautiful woman is the very same knight who rapes a woman at the beginning of the tale 24, this ending can be somewhat disappointing because it does not appeal to our modern sense of justice. The “loathly lady“ who forced the knight into marriage gives in to his wishes only after he has granted her the choice to do whatever she pleases for the rest of her life. 25

This ending seems to be in line with what the “loathly lady“ revealed to be what women want the most, which the knight then tells the Queen:

“Wommen desiren to have sovereintee

As wel over hir housbonde as hir love

And for to been in maistrye him above.”26

The words “sovereintee” and “maistrye” seem to indicate that women will have their men kneel at their feet as servants, but let’s take a look at what actually happens in this happily ever after.

First, the knight’s concession to the “loathly lady:”

“I putte me in your wise governaunce

Cheseth youreself which may be moost plesaunce,

And moost honour to yow and me also.

I do no fors the wheither of the two

For as yow liketh, it suffiseth me.“27

Now, a closer look at how they live happily ever after:

“And she obeyed him in every thing

That might do him plesance or liking

And thus they live unto hir lives ende

In parfit joye–“28

The result of both of these passages is a happily ever after between husband and wife in which each partner is given “mutual obedience and respect.” This, more than anything else, confirms that the Wife of Bath is a romantic idealist who doesn’t seek complete female overthrow of the patriarchy, but rather strives for equality within marriage.29

The Wife of Bath’s personal experience here is visible in the parallels between this ending and the ending of the life story she tells in her prologue. After the physical altercation with her fifth husband, Jankin, Alisoun falls unconscious, comes back to and hits him for the second time, accuses him of murdering her for her property, and then plays dead.30

What follows is somewhat ambiguous; the Wife of Bath glosses over the action, simply stating that they came to an agreement after much care and woe:

“He yaf me al the bridel in min hond,

To han the governaunce of hous and lond“31

She goes on to tell what Jankin said of this:

“Do as thee lust the terme of al thy lif;

Keep thin honour, and keep eek min estaat,”32

This happily ever after is almost identical to the wording the Wife of Bath uses to describe the happily ever after at the end of her tale, particularly given that the Wife after this states that they never again fought and that she was, from then on, the most pleasant and obedient wife from Denmark to India.33

In both endings, the wife does not turn her husband into a servant but rather achieves equality, which is a pretty big deal given the time period.

(For more on how this equality was unconventional for the time, see the Wifehood page)

1.Chaucer, “The Wife of Bath Prologue,” III. 621-25. For modern translation see, https://sites.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/teachslf/wbt-par.htm.

2.O’Donoghue, “Love and Marriage,” 242.

3.O’Donoghue, “Love and Marriage,” 240.

4.Blamires, “Sexuality,” 208.

5.Blamires, “Sexuality,” 209.

6.O’Donoghue, “Love and Marriage,” 245.

7.Blamires, “Love, Marriage, Sex, and Gender,” 19.

8.Blamires, “Love, Marriage, Sex, and Gender,” 216.

9.Blamires, “Love, Marriage, Sex, and Gender,” 20.

10.Chaucer, “The Wife of Bath’s Prologue,” III. 160-63.

11.McSheffrey, “Widows, Widower’s, and Remarriage,” 54-55.

12.Chaucer, “Wife of Bath’s Prologue,” III. 511-14. For modern translation see, https://sites.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/teachslf/wbt-par.htm.

13.Chaucer, “Wife of Bath’s Prologue,”III. 149-50.

14.Dinshaw, “The Pardoner Takes on a Wife,” 131.

15.Chaucer, “The Wife of Bath’s Prologue,” III. 1.

16.Chaucer, “The Wife of Bath’s Prologue,” III. 165.

17.Dinshaw, “The Trouble with Girls,” 91.

18.Dinshaw, “The Pardoner Takes on a Wife,” 130.

19.Dinshaw, “The Pardoner Takes on a Wife,” 130.

20.Cooper, Structure. 126.

21.Cooper, Structure. 128.

22.Chaucer, “The Wife of Bath’s Tale.” III.1113-16. For modern translation see, https://sites.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/teachslf/wbt-par.htm.

23.Chaucer, “The Wife of Bath’s Tale.” III.1257-58.

24.Chaucer, “The Wife of Bath’s Tale.” III.886-87.

25.Chaucer, “The Wife of Bath’s Tale.” III.1230-1249.

26.Chaucer, “The Wife of Bath’s Tale.” III.1038-40.

27.Chaucer, “The Wife of Bath’s Tale.” III.1231-35.For modern translation see, https://sites.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/teachslf/wbt-par.htm.

28.Chaucer, “The Wife of Bath’s Tale.” III. 1255-58.

29.Cooper, Structure. 128-28.

30.Chaucer, “The Wife of Bath’s Prologue.” III.792-810

31.Chaucer, “The Wife of Bath’s Tale Prologue.” III.811-14.

32.Chaucer, “The Wife of Bath’s Tale Prologue.” III.821-822.

33.Chaucer, “The Wife of Bath’s Tale Prologue.” III.822-25.

References:

Blamires, Alcuin. “Love, Marriage, Sex and Gender.” In Chaucer and Religion, 3-23. Edited by Helen Phillips. Cambridge: D. S Brewer, 2010.

Blamires, Alcuin. “Sexuality.” In Chaucer: An Oxford Guide. Edited by Steve Ellis, 208-23. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Canterbury Tales, “The Wife of Bath’s Prologue and Tale.” Edited by Jill Mann, Penguin Books Ltd, 2005.

Cooper, Helen. The Structure of the Canterbury Tales. Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 1983.

Dinshaw, Carolyn. “The Pardoner Takes on a Wife.” In Getting Medieval Sexualities and Communities, Pre- and Postmodern, 126-136. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999.

Dinshaw, Carolyn. “The Trouble with Girls.” In Getting Medieval Sexualities and Communities, Pre- and Postmodern, 87-93. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999.

McSheffrey, Shannon. “Widows,Widowers, and Remarriage.” Marriage, Sex, and Civil Culture in Late Medieval London, 54-58. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

O’Donoghue, Bernard. “Love and Marriage.” In Chaucer: An Oxford Guide. Edited by Steve Ellis, 239-52. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.