Anti-Semitism

Understanding the Puppet Master:

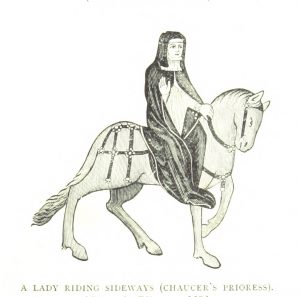

When coming across the Prioress in Chaucer’s famous Canterbury Tales, it quickly becomes apparent that there is quite a bit to unpack. Both she and her tale raise many questions about Chaucer’s motivations for writing the tale, as well as what his own ethical beliefs were. However, the Prioress – like many of the other pilgrims – is an example of Chaucer’s ability to create a dividing line between himself as the author, and the individual telling the story. Chaucer the author figuratively separates himself from the tale almost entirely, cleverly putting on the mask of “Chaucer the Pilgrim,” a technique highlighted in multiple academic articles, and is a primary reason for the debate behind “whose” opinions are being expressed as each pilgrim tells their story.[1] He provides the perfect kind of agency for the reader as they join him in the audience; an observer, just as new to the characters and their tales as the readers are. He mentions in the general prologue that “Whoso shal telle a tale after a man / He moot reherce as ny as evere he kan / Everich a word, if it be in his charge / … Or ellis he moot telle his tale untrewe”[2] This is supposed to clarify that everything he’s going to say next is what he recalls plainly and to the best of his memory, trying to make sure his audience knows that what’s coming next is authentic and as accurate as possible considering it’s a secondhand story.

Antisemitism in the Prioress’s Tale:

Keeping in mind that Chaucer the author has placed the story in the hands of Chaucer the Pilgrim (also commonly interchanged with “Chaucer the Narrator”) and not necessarily himself, the Prioress’s Tale ignites an interesting debate around the anti-Semitic nature of the story.

Factors contributing to this argument:

|

The Prioress as the “storyteller”

|

The Prioress is the head of her convent, but ironically presents herself as “a child of twelve months old, or lesse.” This ties into the idea that, as a devout Catholic, she is merely a infant in the eyes of God and Mary, with reverence to Mary as the overarching theme of her prologue. Because infants are subject to the will and likeness of their parents, the idea in invoked that her tale to follow is that the implications surrounding Jewish people are not her opinion, but rather an accurate depiction of the way things are perceived through the eyes or her faith.[3] |

|

The Blood Libel Tale

|

The Prioress’s tale is part of a larger medieval genre of “Miracles of the Virgin,” but more specifically a sub-genre known as “blood libel” tales.[4] These are stories in which innocent blood is shed by non-christians in efforts to portray them as merciless monsters. Chaucer the author creates his own version of the tale using this template. Catholicism had a forceful and deadly hand in the culture of the time as a result of the crusades. The spread of stories like this helped Catholicism maintain its relevance and used pathos to maintain an emotional hook in its followers. The audience in Chaucer’s time presumably knew these types of tales well and knew to interpret them because the theme would have been instantly recognizable to most.[5] |

|

Chaucer’s (the author) personal religious beliefs and influences |

Chaucer was a well traveled man, and had experience within different cultures as he held a relatively high political position within parliament, one that required him to travel and uphold the interests of his government. During these travels, Chaucer spent time in Spain, where a significant number of Jews served in diplomatic and administrative posts that were not unlike the ones that he held himself.[6] This is not supportive of the argument that Chaucer was an individual in support of anti-Semitism, because the positions he held would have required not only interaction, but collaboration with Jewish officials during his time. However, just because Chaucer might have interacted with Jews professionally in his travels, does not necessarily mean he liked them or supported them. Mirroring the views of many of his countryman, it was more than likely that even though he might have met a Jew, doesn’t necessarily make him not anti-Semitic. |

On top of considering these factors, it’s also important to define the “type” of anti-Semitism exhibited within the tale. It’s important to keep in mind that medieval anti-Semitism relies on different core beliefs than its modern 19th century counterpart. In the Middle Ages, the “offense” was not being of Jewish descent, it was believing in Judaism. Technically, a practicing Jew could still achieve “salvation” through means of conversion to the “correct” faith.[7] Contrastly, “modern” anti-Semitism is more so rooted in actual racism. However, both versions seem to share the same tactics of using old anti-Semitic folklore and stereotypic imagery of Jewish people. Both defile the image of Jews, painting them as inherently evil, greedy, and guilty of usury with no moral boundaries. Their objectives are to overthrow the “heroic” faith of Christianity.[8]

Click below to proceed to an informative analysis of how anti-Semitism manifests itself within the tale!

[1] Alexander, Philip S. “Madame Eglentyne, Geoffrey Chaucer and the Problem of Medieval Anti-Semitism.” Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 74. 1 (1992): 117.

[2] Chaucer, Geoffrey. “The Prioress’s Prologue.” The Canterbury Tales. Edited by F.N. Robinson. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1957, 161.

[3] Price, Merrall Llewelyn. “Sadism and Sentimentality: Absorbing Antisemitism in Chaucer’s Prioress.” The Chaucer Review 43. 2 (2008): 197–214.

[4] Alexander, Philip S. “Madame Eglentyne,” 119

[5] Ibid., 118

[6] Besserman, Lawrence L. ‘‘Chaucer, Spain, and the Prioress’s Antisemitism.’’ Viator 35 (2004): 340.

[7] Alexander, Philip S. “Madame Eglentyne,” 111.

[8] Ibid., 110.